A load-bearing wall is any wall that supports vertical loads beyond its own weight (like the floor or roof above). That’s the code definition in the International Residential Code’s definition section for a “load-bearing wall.”

Safety first (important)

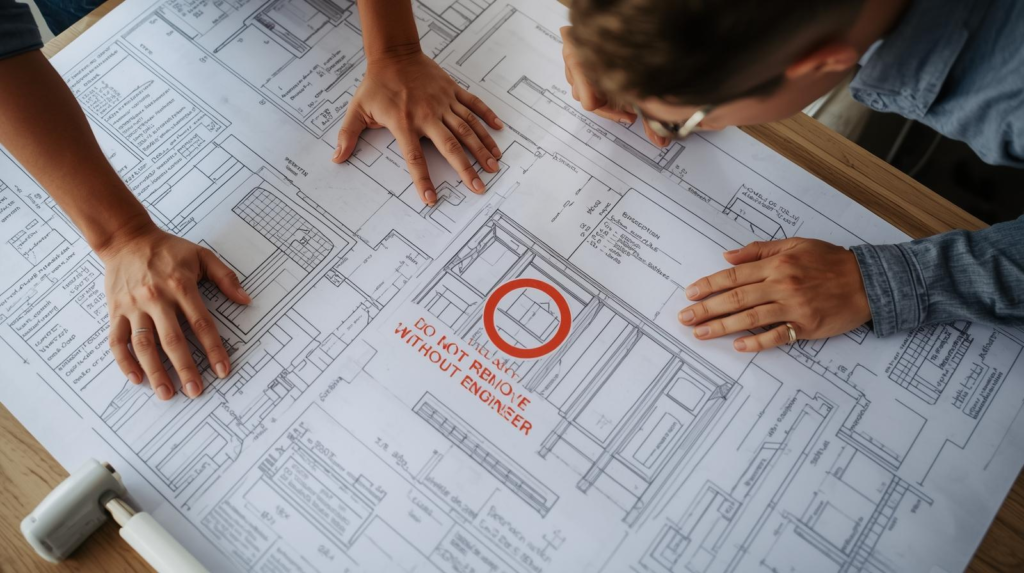

If you’re planning to remove, widen, or cut a big opening in a wall, treat it as load-bearing until proven otherwise. Load changes can require engineered beams/headers and proper supports—code rules for headers and support are addressed in the IRC’s R602.7 Headers section and discussed structurally in HUD’s Residential Structural Design Guide.

The quickest way to be sure

1) Check the original plans (best evidence)

If you can get them, structural drawings or framing plans often show bearing lines, beams, and posts. This is the most reliable “homeowner” method because it reflects the intended load path (see HUD’s overview of residential structural systems in the Residential Structural Design Guide and FEMA’s explanation of a continuous load path).

Field checks you can do without opening the wall

These are strong clues, not absolute proof. Use multiple checks together.

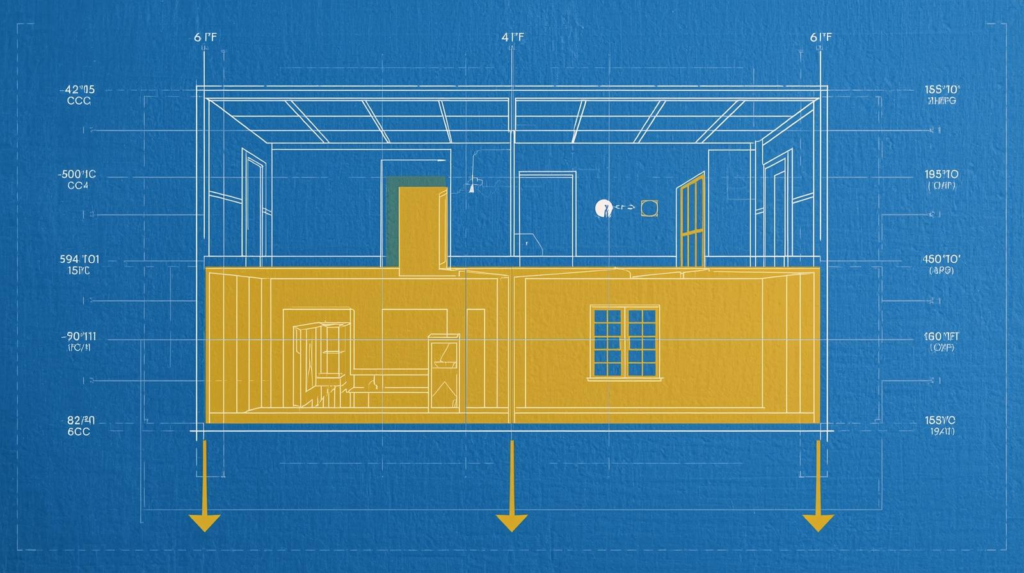

2) Look at what’s directly below the wall

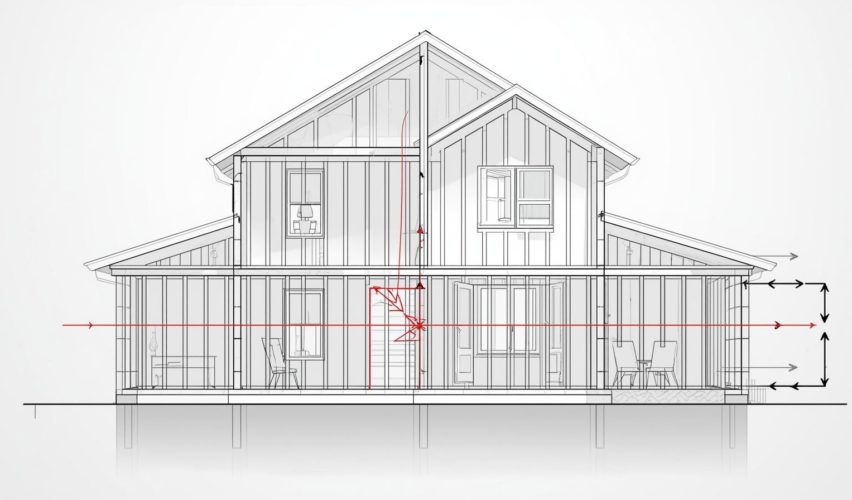

A load-bearing wall usually transfers load down to something solid—a beam/girder, another bearing wall, posts/columns, or the foundation. This “downward load path” idea is standard structural guidance (see the load-path explanation in HUD’s Residential Structural Design Guide and FEMA’sl oad path fact sheet).

How to check:

- Go to the basement/crawlspace (or the floor below).

- Find the wall’s location and look for a beam, girder, or posts aligned under it.

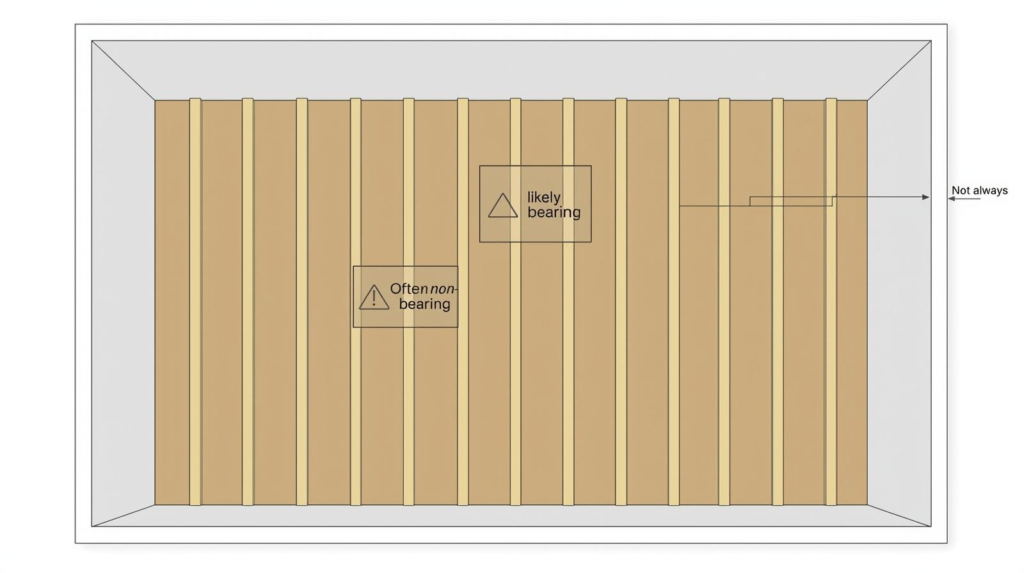

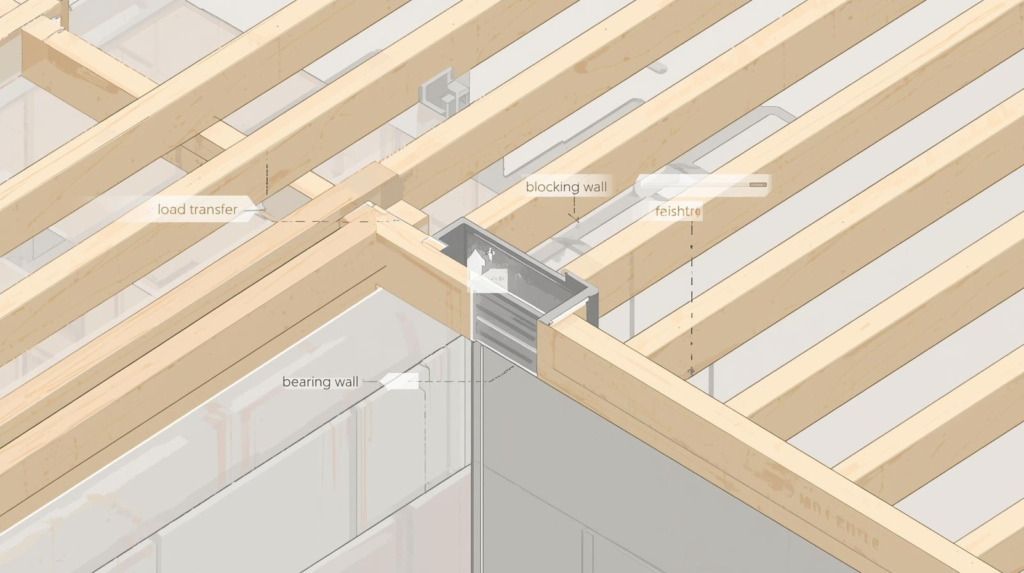

3) Check the direction of the joists above (a classic clue)

A common rule of thumb:

- If the wall runs perpendicular to floor/ceiling joists, it’s often load-bearing

- If it runs parallel, it’s often not—but it still can be bearing if joists splice over it or if blocking transfers load

This “perpendicular = likely bearing” heuristic is widely used in homeowner guidance (for example, Better Homes & Gardens’ explanation and The Spruce’s explanation). The reason it’s not foolproof is that engineered floor systems can carry loads to bearing points in multiple ways—APA documents show that blocking/squash blocks may be required where bearing walls occur relative to I-joists (see APA’s Blocking for I-joist Floor Systems (PDF) and APA’s Performance Rated I-Joists guide (PDF)).

How to check:

- In an unfinished basement/attic, visually identify joist direction.

- If finished, a stud finder with joist-scan can help map joist direction, but treat it as a hint, not proof (see the “joist direction” approach described in BHG’s guide).

4) Look for “stacking” (walls lining up across floors)

If the same wall line appears directly above/below on multiple stories, that often indicates a continuous load path down to the foundation (a core concept in FEMA’s load path explanation and HUD’s structural system overview).

How to check:

- Stand on each floor and see whether the wall sits in the same place relative to stairs, exterior walls, or other fixed references.

5) Check for beams, girder pockets, or joist splices landing on the wall

A wall may be bearing even if it runs parallel to joists when:

- A beam ends over it, or

- Joists are supported by blocking/squash blocks that transfer loads into that wall

This is consistent with APA guidance about blocking under/at bearing locations for I-joist systems (see APA’s Blocking for I-joist Floor Systems (PDF) and the related load-transfer notes in APA’s Performance Rated I-Joists guide (PDF)).

What it can look like in the basement/ceiling framing:

- A doubled member (beam) running under joists

- Posts/columns under that beam

- Concentrated blocking near the wall line

“Clues” inside the wall (helpful but not decisive)

These are suggestive, not guarantees—builders vary.

6) Large headers over openings can suggest bearing

Openings in load-bearing walls typically require properly sized headers and support details; the IRC covers header requirements and support conditions in R602.7 Headers, and APA guidance distinguishes header use in bearing vs non-bearing contexts (see the APA wall guide excerpt: Engineered Wood Wall Construction Guide (PDF)).

Practical takeaway:

- A substantial header over a doorway can be a clue the wall is carrying load—but small headers can exist in bearing walls too, depending on span/load.

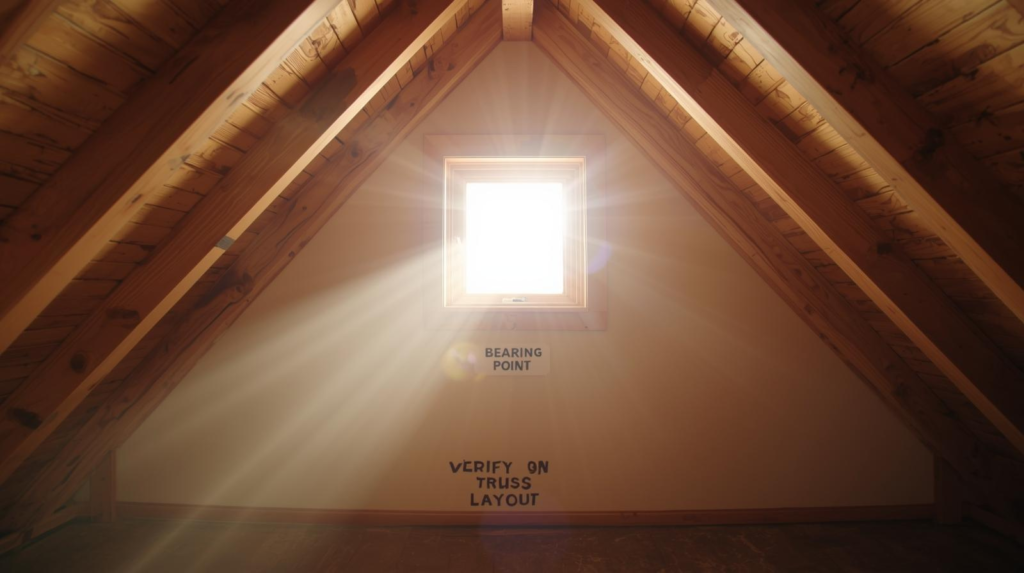

Roof/truss note (common confusion)

Many homes use roof trusses designed to bear on exterior walls, but some truss layouts include interior bearing locations that should be clearly shown on layouts or engineering documents. Industry guidance notes that when internal walls are used for bearing, it’s identified in the truss layout (see the truss-installation guidance statement in the MiTek Roof Truss Installation Guide (PDF) and the bearing/support concepts in the truss standard ANSI/TPI 1 (PDF)).

A simple decision checklist

A wall is more likely load-bearing if two or more of these are true:

- It lines up with a beam/posts or foundation support below (load-path logic from HUD’s Residential Structural Design Guide and FEMA’s load path fact sheet).

- It runs perpendicular to joists above (common heuristic described by BHG and The Spruce).

- There’s evidence of bearing-wall detailing in the floor framing (blocking/squash blocks near that wall line), consistent with APA’s I-joist blocking guidance (PDF) and APA’s I-joist guide (PDF).

- The same wall location stacks on multiple floors (load-path concept in FEMA’s load path fact sheet and HUD’s guide).

When to stop DIY and call a pro

Get a structural engineer (or qualified contractor working with one) if:

- You want to remove a wall or create a wide opening

- The house has multiple stories, unusual spans, or engineered framing

- The wall is near stairs, large openings, or you see beams/columns nearby

That’s because changing a bearing wall usually requires redesigning the load path with proper headers/beams and supports—covered conceptually by HUD’s Residential Structural Design Guide and in prescriptive header rules like IRC R602.7.

Summary

To figure out if a wall is load bearing, combine the strongest evidence first (plans + what supports the wall below) with practical framing clues (joist direction, stacked walls, and bearing-style blocking/details). If you’re planning to remove or alter the wall, confirm with an engineer—because the safe fix is about maintaining a continuous load path to the foundation.